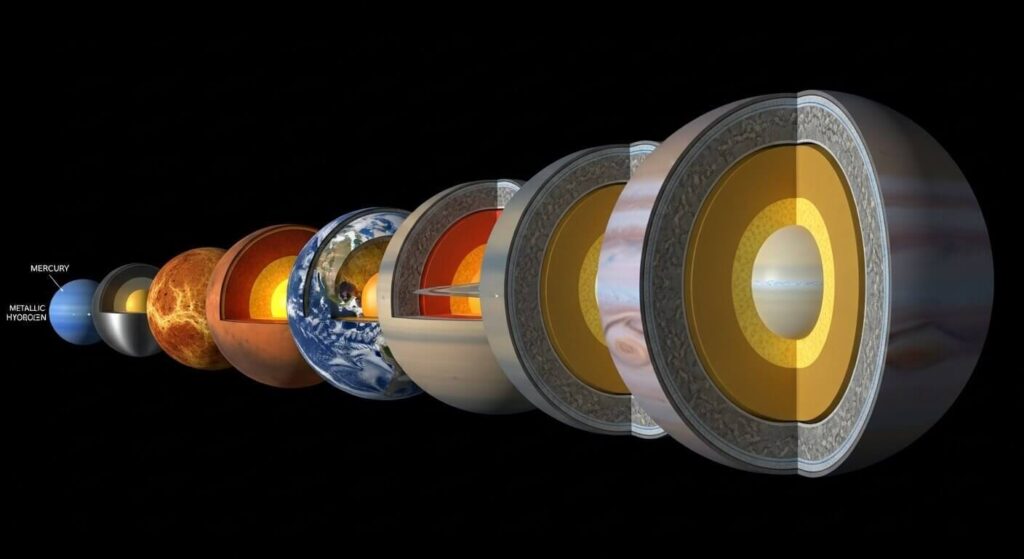

Ever wonder what’s inside the planets? We virtually slice open the solar system, from Mercury‘s iron core to Neptune’s icy mantle. Explore the definitive guide to the internal structure of every planet.

We spend our lives looking up at the planets as distant points of light or beautiful orbs in telescope images. But have you ever truly wondered what’s inside them? What would you see if you could slice a planet in half? It’s a question that feels like science fiction, but it’s the very core of planetary science. The “guts” of a planet tell its entire life story—how it was born, how it evolved, and why it ended up so different from its neighbors.

Understanding the internal structure of solar system planets isn’t just a curiosity; it explains everything we see on the surface. Why does Earth have a magnetic field that protects life, while Mars doesn’t? Why is Jupiter a raging magnetic monster? The answers lie deep underground.

In this guide, we’ll take a comprehensive journey to the center of every planet in our solar system. We’ll explore the two major families—the dense, rocky worlds and the enormous, swirling giants—and uncover the expert-backed theories and recent discoveries (like data from NASA’s Juno and InSight missions) that are pulling back the curtain on these hidden realms. Let’s start digging.

Table of Contents

- The Two Planetary Families: Why Are They So Different?

- The Rocky Inner Worlds: Our Solar System’s Core

- The Outer Giants: Uncovering the Gas & Ice Layers

- Conclusion: Why a Planet’s Interior is Everything

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) About Planetary Interiors

The Two Planetary Families: Why Are They So Different?

The solar system is fundamentally split into two groups. In the “inner city”—closer to the Sun—we have the terrestrial (rocky) planets: Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars. In the “outer suburbs,” we have the giant planets. But even they are split: the gas giants (Jupiter, Saturn) and the ice giants (Uranus, Neptune).

This division happened early on. In the hot, inner solar system, only heavy materials like rock and metal could condense. Farther out, beyond the “frost line,” it was cold enough for lighter materials—like hydrogen, helium, and water “ice”—to form massive planets. All planets underwent a process called differentiation, where heavier materials (like iron) sank to the center to form a core, leaving lighter materials (like silicate rock or gas) to form the outer layers. This simple process created the layered structures we see today.

The Rocky Inner Worlds: Our Solar System’s Core

All terrestrial planets share a basic structure: a metallic core at the center, a thick, rocky mantle surrounding it, and a thin, solid crust on the surface. But the size and state of these layers make all the difference.

Mercury: The Disproportionate Iron Planet

If you sliced Mercury open, you’d be stunned. It’s often called the “metal meatball” of the solar system. Its internal structure is completely dominated by a massive iron core that is thought to be about 85% of the planet’s entire radius. To put that in perspective, Earth’s core is only about 50% of its radius. This leaves only a thin silicate mantle and crust. Scientists believe a giant impact early in its history may have blasted away most of its original rocky mantle, leaving this iron-heavy remnant behind. Surprisingly, this massive core generates a weak, but active, magnetic field.

Venus: Earth’s Stagnant, Toxic Twin

Venus is Earth’s size, but its interior is a mystery wrapped in an enigma (and a 465°C toxic atmosphere). Its internal structure is believed to be very similar to Earth’s: an iron-nickel core (partially liquid?), a rocky mantle, and a crust. The biggest difference? Venus appears to lack Earth-style plate tectonics. Its crust seems to be a “stagnant lid”—one solid piece. This may prevent heat from escaping efficiently, possibly leading to catastrophic, planet-wide volcanic eruptions that resurface the entire globe every few hundred million years.

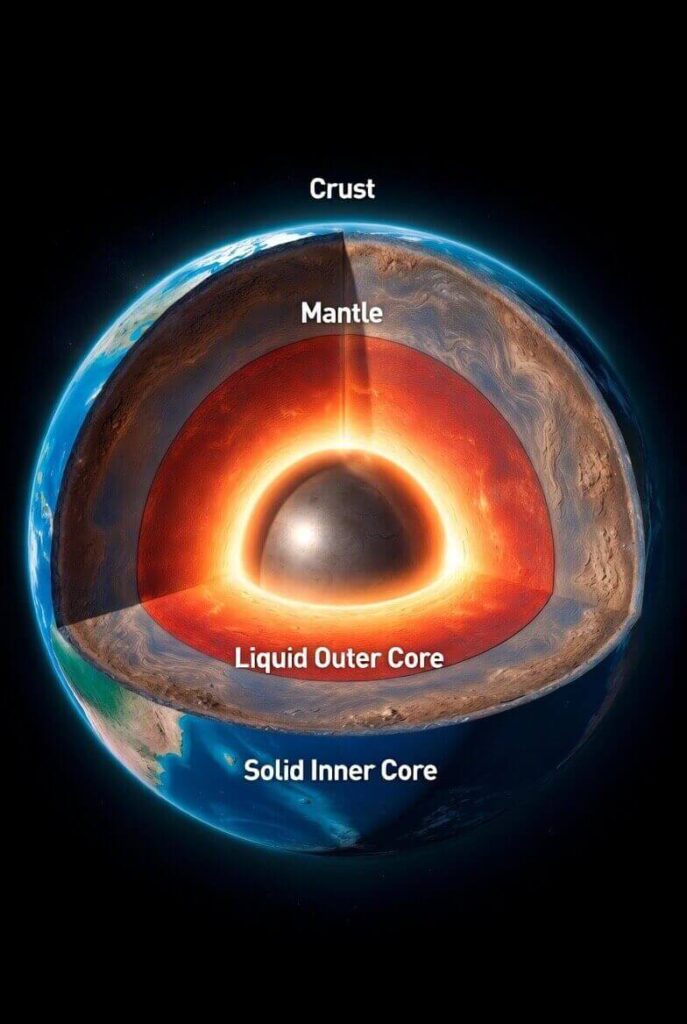

Earth: Our Active, Life-Giving Interior

Our home is the most dynamic of all. Earth’s internal structure is the key to life. We have:

- A Solid Inner Core: A ball of solid iron-nickel, as hot as the Sun’s surface, but kept solid by immense pressure.

- A Liquid Outer Core: This swirling, convective layer of liquid iron acts like a giant dynamo. As it churns, it generates Earth’s strong magnetic field, which shields us from harmful solar radiation.

- A Convecting Mantle: A thick layer of hot, “plastic-like” rock (think of it as a cosmic lava lamp) that moves in slow-motion currents.

- A Tectonic Crust: The mantle’s movement drives plate tectonics on the crust, recycling minerals, driving a climate-regulating carbon cycle, and creating volcanoes.

Mars: The Cooling Red Planet’s Surprising Core

For decades, Mars was thought to be a geologically “dead” planet with a cold, solid core. The NASA InSight lander completely changed our understanding of the Martian internal structure. By listening for “Marsquakes,” InSight confirmed that Mars has a large, liquid iron core. This was a shock! It’s less dense than Earth’s, meaning it’s mixed with lighter elements like sulfur. However, Mars is smaller than Earth, so it cooled off faster. Its mantle is less active, and its liquid core isn’t convecting in a way that generates a global magnetic field, leaving its surface exposed to radiation.

The Outer Giants: Uncovering the Gas & Ice Layers

The giants have no “solid” surface to stand on. Their “interiors” begin the moment you drop below the cloud tops, where pressures and temperatures skyrocket to truly mind-boggling levels.

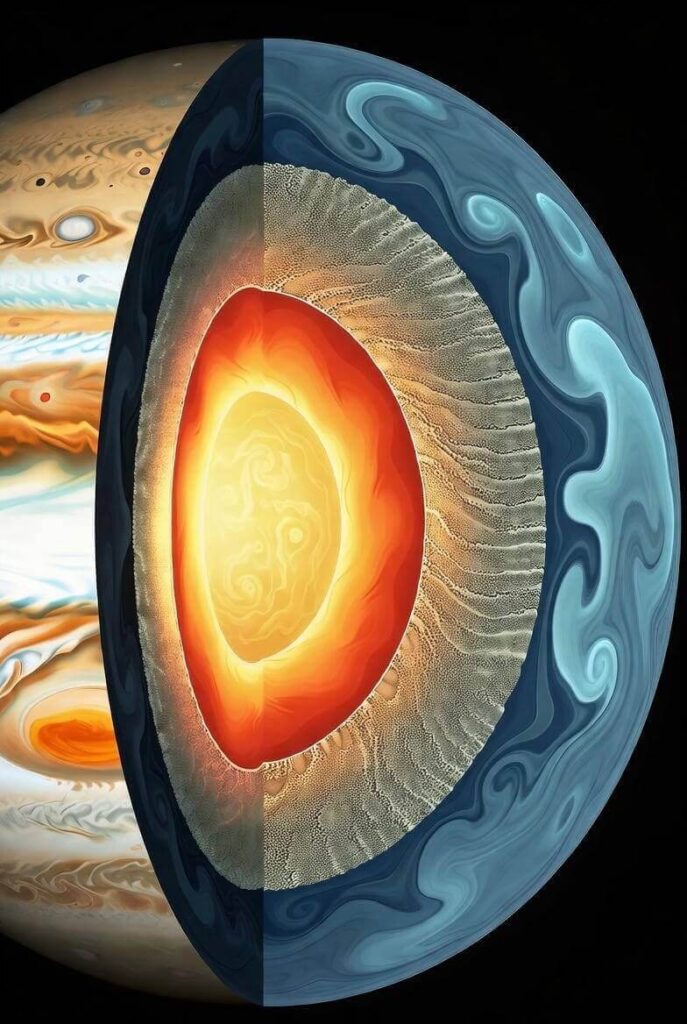

Jupiter: The King with a Metallic Hydrogen Heart

Jupiter’s internal structure is a lesson in extreme physics. As you descend through its massive hydrogen and helium atmosphere:

- The gas compresses into a planet-spanning ocean of liquid hydrogen.

- Go deeper, and the pressure (over 2 million times Earth’s atmosphere) becomes so intense it crushes the hydrogen atoms. The electrons are squeezed free, and the hydrogen begins to conduct electricity like a metal. This is the “electric jelly” layer, or metallic hydrogen.

- This swirling ocean of metallic hydrogen is what generates Jupiter’s immensely powerful magnetic field, the largest in the solar system.

- Core: Data from the Juno spacecraft suggests Jupiter’s core isn’t a solid, distinct ball of rock. It may be a “fuzzy” or “dilute” core, where heavy elements of rock and ice are mixed into the metallic hydrogen above it.

Saturn: The Lighter Giant with Helium Rain

Saturn is a less extreme version of Jupiter. Its internal structure is similar: atmosphere, liquid hydrogen, then metallic hydrogen, and a core. However, because Saturn is less massive, the pressure is lower. You have to go much deeper to find the metallic hydrogen layer. Saturn is also strangely hot—it radiates more energy than it gets from the Sun. The leading theory? It’s raining inside. In the frigid upper layers, helium condenses into “rain” that falls toward the core, releasing heat from friction as it sinks.

Uranus & Neptune: The ‘Ice Giant’ Mantles

Uranus and Neptune are not gas giants. They are a distinct class: Ice Giants. While they have thick hydrogen/helium atmospheres, their “insides” are dominated by “ices.”

Don’t think of ice cubes. Their vast mantles are a hot, sludgy, “superionic” soup of water ($H_2O$), methane ($CH_4$), and ammonia ($NH_3$) under extreme pressure. In this state, the water molecules break apart, allowing hydrogen ions to flow freely like a liquid, while the oxygen forms a solid lattice. This bizarre “hot, dark ice” (superionic water) is what’s thought to generate the strange, off-center magnetic fields of both planets.

At the very center of both ice giants lies a small, hot, rocky core roughly the mass of the Earth.

Conclusion: Why a Planet’s Interior is Everything

As we’ve seen, you can’t judge a planet by its cover. The internal structure of a solar system planet dictates its destiny. A planet’s core and mantle control its magnetic field, its surface geology, its atmospheric evolution, and, in Earth’s case, its ability to host life.

From Mercury’s giant iron heart to Jupiter’s “fuzzy” core and Neptune’s superionic ice mantle, each planet is a unique and dynamic world. As we continue to send probes and use new observational techniques, we’re no longer just looking *at* these worlds—we’re looking *through* them.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) About Planetary Interiors

Q: How do we know the internal structure of planets we’ve never been to?

A: We use several clever, indirect methods!

1. Gravity: Spacecraft (like NASA’s Juno and Cassini) measure tiny variations in a planet’s gravity field. This “gravity mapping” tells scientists how mass is distributed inside—revealing the size and density of the core.

2. Magnetic Fields: The presence, strength, and shape of a magnetic field tell us if a planet has a liquid, conductive interior (like Earth’s liquid iron or Jupiter’s metallic hydrogen).

3. Seismology: On Earth and Mars (via the InSight lander), we measure “earthquakes” or “marsquakes.” The way these seismic waves travel and bounce off different layers reveals the boundaries of the crust, mantle, and core.

4. Computer Modeling: Scientists use lab data on how materials behave under extreme pressure to build computer models that must match the planet’s observed mass, size, and temperature.

Q: Do all solar system planets have a core?

A: Yes, all evidence points to the fact that every planet in our solar system (and even many dwarf planets) has undergone differentiation, resulting in a dense core. The composition and state (liquid or solid) of that core are what make each planet unique.

Q: What is metallic hydrogen, and is it a real thing?

A: Metallic hydrogen is a very real theoretical state of matter (an allotrope of hydrogen) that is created under immense pressure. It’s not a “metal” in the traditional sense, but under pressures millions of times greater than on Earth, hydrogen’s single electron is squeezed free from its atom. This creates a “sea” of free-flowing electrons, allowing the hydrogen to conduct electricity just like copper or iron. This is the engine for Jupiter’s and Saturn’s magnetic fields.

Q: Why is Earth’s internal structure so important for life?

A: Earth’s active interior is arguably the single most important reason life exists here. The churning, liquid outer core creates our magnetic field, which acts as a shield, deflecting the “solar wind”—a constant stream of charged particles from the Sun that would otherwise strip away our atmosphere and boil our oceans. Without our active core, Earth would likely be a cold, barren, irradiated rock, much like Mars.